Nikola Benin

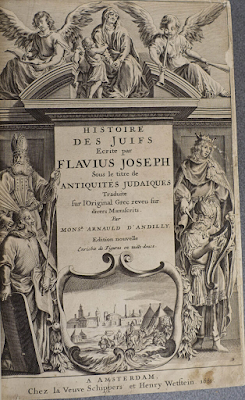

Guerrilla fighter and defector, opportunist, propaganda writer and interpreter of prophecies: Flavius Josephus was one of the most fascinating and contradictory figures of the Roman imperial period. He didn’t rise to literary fame until centuries after his death and, thanks to his monumental work ‘Antiquities of the Jews’, that fame lasted until well into the modern era. Also Arnauld d’Andilly, one of the best translators in 17th-century France, tried his hand at the text. His refined French turned Josephus’s somewhat simple style into something much grander. But in any case, d’Andilly had very different reasons for translating this text.

Flavius Josephus: From Resistance Fighter to Mainstream Author

Jerusalem-born priest Flavius Josephus was just thirty years old when, in early AD 67 during what is known as the First Jewish–Roman War, he found himself facing a challenge of epic proportions: he was tasked with defending Galilee against Rome’s far superior, 60,000-strong army. Of course, Josephus failed and was captured. He prophesied that the Roman general Vespasian would become Emperor. In doing so, this guerrillero bet on exactly the right horse. After the war was over, Vespasian secured the imperial throne and Flavius Josephus was brought to Rome as a prisoner of war, but a highly respected one.

There, he began his career as a writer, financed by a pension from the new ruling family. As such, the Flavians were portrayed rather favourably in his work ‘The Jewish War’. Flavius Josephus wrote in Greek, his native languages were Aramaic and Hebrew. In terms of style, he couldn’t keep up with Rome’s literary elite at all. His second work, ‘Antiquities of the Jews’, once again fell far behind linguistically and did not seem to leave any sort of lasting impression on his contemporaries.

This comes as no surprise. The title ‘Antiquities of the Jews’ was based on the ‘Roman Antiquities’ by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who combined Roman and Greek history and was enormously successful. The first half of Flavius Josephus’s twenty volumes, on the other hand, faithfully tell the Bible’s account of world history. For non-Jewish people, this may have been entertaining at best, but not at all intellectually stimulating. Like so many writers, he wouldn’t live to see the success of his work – but it did succeed.

The ‘Antiquities of the Jews’: An Alternative Bible

For the first few centuries after the invention of the letter press, Latin works were more popular among ancient historians than Greek ones. This was simply based on the language proficiency of the readers. However, the works of Flavius Josephus were the two clear favourites out of all the Greek writers. Why?

It’s very simple: for one thing, the first half of ‘Antiquities of the Jews’ could pass for an ‘alternative Bible’. From 1559 onwards, translations of the Bible first had to be approved by the Holy Office of the Inquisition, while Josephus’s works could be printed by anyone at any time. And there was no shortage of translations into local languages.

In the second half of his ‘Antiquities of the Jews’ Josephus also covers the period in which Jesus lived. It could therefore be considered the only somewhat contemporary historical source for the life of Jesus. The Christian theologians were wary of posthumously converting Flavius Josephus into a Christian, as in the case of Virgil, for example. As a non-Christian, his account carried a lot more weight.

Arnauld d’Andilly: Finance Expert and Language Wizard

Flavius Josephus’s translator, Robert Arnauld d’Andilly (1589-1674), was just as impressive as Josephus himself. Born into a respectable family, he was able to join the Council of State at the French court in 1611. He owed this promotion to rather exceptional circumstances. King Henry IV had been murdered the previous year. His widow, Marie de’ Medici, was confirmed as Regent on behalf of her son Louis XIII, who was just nine years old. As a finance expert, Robert Arnauld d’Andilly advised the Regent in the Council of State and was as renowned at court for his weakness for beautiful women as he was for his elegant verses.

This is what the abbey Port-Royal-des-Champs looked like a little later. Painting by Louise-Madeleine Horthemels, around 1710.

Then things changed: after the death of his wife and his close friend, court life became very bland for him. In 1644, d’Andilly retreated to the Cistercian abbey Port-Royal-des-Champs near Versailles, where he lived as a sort of hermit. The abbey was presided over by his sister Angélique. It was a hub for a particularly strict branch of Catholicism, known as Jansenism, and as such it attracted some great thinkers such as Blaise Pascal and Jean Racine. These thinkers would retreat as ‘Solitaires of Port-Royal’ to the same place where Robert Arnaud d’Andilly found leisure for his translation work.

Няма коментари:

Публикуване на коментар