Nikola Benin, Ph.D

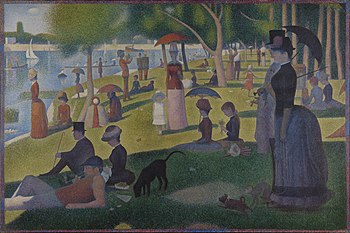

A Sunday Afternoon on

the Island of La Grande Jatte (French: Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la

Grande Jatte) is Georges Seurat's most famous work1.

Seurat painted A Sunday Afternoon between May 1884 and March 1885, and from

October 1885 to May 1886, focusing meticulously on the landscape of the park.

He reworked the original and completed numerous preliminary drawings and oil

sketches2. He sat in the park, creating numerous sketches of the

various figures in order to perfect their form.

The painting was first exhibited at the eighth (and last)

Impressionist exhibition in May 1886, then in August 1886, dominating the

second Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, of which Seurat had been a founder in 1884.

Inspired by research in optical and color theory, he

juxtaposed tiny dabs of colors that, through optical blending, form a single

and, he believed, more brilliantly luminous hue. He believed that this form of

painting, called Divisionism at the time (a term he preferred) but now known as

Pointillism, would make the colors more brilliant and powerful than standard

brushstrokes. The use of dots of almost uniform size came in the second year of

his work on the painting, 1885–86. To make the experience of the painting even

more intense, he surrounded the canvas with a frame of painted dashes and dots,

which he, in turn, enclosed with a pure white wood frame, similar to the one

with which the painting is exhibited today. The very immobility of the figures

and the shadows they cast makes them forever silent and enigmatic.

Bathers at Asnières, completed shortly before, in

1884. Whereas the bathers in that earlier painting are doused in light, almost

every figure on La Grande Jatte appears to be cast in shadow, either under

trees or an umbrella, or from another person. For Parisians, Sunday was the day

to escape the heat of the city and head for the shade of the trees and the cool

breezes that came off the river. And at first glance, the viewer sees many

different people relaxing in a park by the river. On the right, a fashionable

couple, the woman with the sunshade and the man in his top hat, are on a

stroll. On the left, another woman who is also well dressed extends her fishing

pole over the water. There is a small man with the black hat and thin cane

looking at the river, and a white dog with a brown head, a woman knitting, a

man playing a horn, two soldiers standing at attention as the musician plays,

and a woman hunched under an orange umbrella. Seurat also painted a man with a

pipe, a woman under a parasol in a boat filled with rowers, and a couple

admiring their infant child3.

Some of the characters are doing curious things. The

lady on the right side has a monkey on a leash. A lady on the left near the

river bank is fishing. The area was known at the time as being a place to procure

prostitutes among the bourgeoisie, a likely allusion of the otherwise odd

"fishing" rod. In the painting's center stands a little girl dressed

in white (who is not in a shadow), who stares directly at the viewer of the

painting. This may be interpreted as someone who is silently questioning the

audience: "What will become of these people and their class?" Seurat

paints their prospects bleakly, cloaked as they are in shadow and suspicion of

sin4.

In the 1950s, historian and Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch

drew social and political significance from Seurat's La Grande Jatte. The

historian's focal point was Seurat's mechanical use of the figures and what

their static nature said about French society at the time. Afterward, the work

received heavy criticism by many that centered on the artist's mathematical and

robotic interpretation of modernity in Paris5.

According to historian of Modernism William R.

Everdell:

Seurat himself told a sympathetic critic, Gustave

Kahn, that his model was the Panathenaic procession in the Parthenon frieze.

But Seurat didn't want to paint ancient Athenians. He wanted 'to make the

moderns file past ... in their essential form.' By 'moderns' he meant nothing

very complicated. He wanted ordinary people as his subject, and ordinary life.

He was a bit of a democract—a "Communard," as one of his friends

remarked, referring to the left-wing revolutionaries of 1871; and he was

fascinated by the way things distinct and different encountered each other: the

city and the country, the farm and the factory, the bourgeois and the

proletarian meeting at their edges in a sort of harmony of opposites6.

The border of the painting is, unusually, in inverted

color, as if the world around them is also slowly inverting from the way of

life they have known. Seen in this context, the boy who bathes on the other

side of the river bank at Asnières appears to be calling out to them, as if to

say, "We are the future. Come and join us".

References

1. Kathryn Calley Galitz (2007). Masterpieces of

European Painting, 1800–1920, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan

Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.). p. 177.

2. H. Dorra and J. Rewald, Seurat, Paris, 1960, p.

156.

3. Burleigh, Robert, Seurat and La Grande Jatte:

connecting the dots, New York: H.N. Abrams in association with the Art

Institute of Chicago, 2004. Print.

4. BBC, The Private Life of a Masterpiece (2005)

Series 4, Georges Seurat: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

5. New York Times, Fire in Modern Museum; Most Art

Safe; 6 Canvases Burned, Seurat's Removed, 16 April 1958.

6. William R. Everdell, The First Moderns: Profiles in

the Origins of Twentieth Century Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago

Press), 66-7.

Няма коментари:

Публикуване на коментар